- The BPL has released the results of a year-long external review of the library's Print Collection by Simmons College professor Martha Mahard. Mahard has now been tasked with conducting an item-by-item inventory of the department. The full report is available here (below the press release text).

- The Criminal podcast this week ("Ex Libris") features booksellers John Crichton, Ken Sanders, and Garrett Scott, talking about the John Charles Gilkey book thefts and Allison Hoover Bartlett's The Man Who Loved Books Too Much. Scott describes the ongoing Gilkey saga as "a low-level brush fire that's never going away," and the podcaster reveals that Gilkey was only recently arrested again on charges related to passing bad checks.

- Big, and excellent news from the American Antiquarian Society: they are no longer requiring permission or licensing agreements before images from their collections can be published. See their Obtaining Digital Images page for the new policy.

- The University of Edinburgh's Centre for the Book has posted a series of short instructional videos about book history, including films on bibliographic format, watermarks, and collation statements.

- The president of the ALA has called on President Obama to nominate a librarian to head the Library of Congress.

- For the first time since 2008, the New York Public Library will receive an increase in city funding for fiscal year 2015.

- The DPLA has received $3.4 million from the Sloan and Knight Foundations to open new service hubs and promote continued expansion.

- Speaking of the NYPL, Scott Sherman has a piece in the Chronicle drawn from his new book about the NYPL, Patience and Fortitude.

- From Bloomberg, "Discovering Harvard's Hidden Treasures," a short video about the Houghton Library and some of the fantastic things in its collections.

- Jay Moschella writes for the BPL's Collections of Distinctions blog about a volume of manuscripts in the library's collections which may be from the library of England's first printer, William Caxton.

- Oxford's Somerville College is crowdfunding the conservation of John Stuart Mill's personal library.

- Emily Levine has a piece in the LA Review of Books, "The Afterlife of a Manuscript."

- German publisher Tredition has released an open-access handbook, Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction.

- AAS Curator of Newspapers Vince Golden talked to the Worcester Telegram & Gazette for their "Sunday Sit-Down" interview.

- The Freedmen's Bureau Project seeks to make 1.5 million documents from the Freedmen's Bureau archives available and searchable online by the end of 2016.

- A set of Chipotle's Cultivating Thought series of short texts by famous authors on the restaurant's paper cups and bags has been donated to Yale's Beinecke Library.

- A copy of the Tyndale New Testament (1537) will be sold at Sotheby's on 15 July; the current owner purchased the volume in 1966 for 25 shillings.

- Andrea Mays talked at the D.C. bookstore Politics and Prose about her book The Millionaire and the Bard last week. Listen here.

- From Ken Kalfus for the New Yorker, "A Book Buyer's Lament."

- Sarah Werner announces at Wynken de Worde that she's left the Folger to work on her Handbook for Studying Early Printed Books, 1450–1800 and developing an open-access website to accompany the book.

- A preprint of Zachary Lesser and Peter Stallybrass' essay "Shakespeare Between Pamphlet and Book" is now available via academia.edu (click "Download" at the upper right).

- Over on the Royal Society's blog The Repository, Fiona Keates highlights Benjamin Franklin's "magic squares" in the Society's collections.

- The University of Iowa has received nearly 18,000 science fiction books from a Sioux Falls collector.

- From Madison Johnson at The New Republic, an interview with photographer Yuri Dojc about his Last Folio project.

- At FiveThirtyEight, David Goldenberg writes about his attempt to get information from the ALA about their statistics on attempts to ban books, which raises good and important questions about how the ALA presents these issues.

- A new website, Transcribing Early American Manuscript Sermons, launched this week.

- Roger Wieck has been named head of the Morgan Library & Musem's Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts.

- Jennifer Maloney writes in the WSJ about the new fonts both Amazon and Google are pushing for their e-reading devices.

- Noah Charney talked to Dave Davies of "Fresh Air" about his new book The Art of Forgery.

Reviews

- The Morgan Library & Museum's new exhibition, "Alice: 150 Years of Wonderland"; review by Randy Kennedy in the NYTimes.

- Thomas Kunkel's Man in Profile; review by John Williams in the NYTimes.

- Stephen Jarvis' Death and Mr. Pickwick; review by Wendy Smith in the WaPo.

- Elif Shafak's The Architect's Apprentice; review by Bruce Holsinger in the WaPo.

- Hugh Aldersey-Williams' In Search of Sir Thomas Browne; review by Jeffrey Collins in the WSJ.

- Alberto Manguel's Curiosity; review by Duncan White in the Telegraph.

- Scott Sherman's Patience and Fortitude; review by Maureen Corrigan for "Fresh Air."

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

An Interesting Preface from 1763

I ran across this interesting preface last week and thought it worth sharing here, given the focus on matters bibliographical. The text appears on pages v–xvi of the satirical novel Memoirs of the Life and Adventures of Tsonnonthouan, a King of the Indian Nation called Roundheads. Extracted from Original Papers and Archives. London: Printed for the Editor, and Sold by J. Knox, at the Three Poets, in the Strand, 1763. My transcription is from the 1974 Garland reprint. The book was published prior to the release of volumes 7–9 of Tristram Shandy, and has been attributed to Charles Johnstone or, more frequently, to Archibald Campbell:

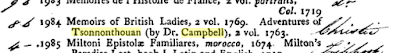

From A Catalogue of the Curious and Extensive Library of the late James Bindley, Esq., F.S.A. (1818), p. 74.

Preface:

[v] The Bookseller having insisted on his prerogative of writing the Title-Page, I wish he had also written the Preface; it would have saved me a task I am by no means fond of. In justice he ought to have done it, for his Title-Page hath rendered a Preface necessary. But he must be excused, on this account; a Preface is always supposed to have some relation to the work it ushers into the world; now a bookseller having commonly as great an aversion as reading the trash he sells to his customers, as a physician has at taking the trash he prescribes to his patients, it is not to be expected a man should write about that which he knows nothing of. This, I can safely say, is the case with my bookseller; I can aver he has not as yet read a sentence of the following work, and in all probability never will. But it [vi] is quite otherwise with the title, as it is by the merits of that alone he thinks he sells the book; and indeed he is in the right to think so, for he seldom knows any thing more of the matter. I have heard a bookseller say he had purchased a pamphlet for half a guinea, tho' he knew not what the pamphlet contained, but he was sure he had made a good bargain, for the title page alone was worth double the money. Indeed it is no wonder that booksellers are the best judges and authors of title-pages in the world, the whole force of their genius, and bent of their study, being directed to nothing else, except, sometimes, a few strictures on the paper, print, and binding; and when a man applies himself entirely to one science, he must necessarily excell in it. For this reason I submitted every thing respecting the title-page to the bookseller; indeed he made enquiries about nothing else, excepting the price. When I first carried him the following sheets in manuscript, he asked me what title I proposed? I made answer, The Life and Adventures of Tsonnonthouan, a Roundheaded Indian. He objected to this as too simple; we must call it Memoirs, said he, for that word implies something of secrecy, and the [vii] publick is always glad of being let into a secret. This being assented to, he next hinted that the hero ought to be dignified with some pompous appellation; I proposed that of Chief of the Roundheads, though not strictly and historically true. The sagacious bookseller was not altogether pleased with this; he said, it referred to something outlandish, and besides, we had but a slender idea of such an office in this country. I was very sensible of the solidity of this objection, so left the matter entirely to himself. Upon which he immediately dubbed Tsonnonthouan King; a name, which notwithstanding some late incidents, has still some regard paid to it, amongst us. It was in vain for me to object that such an office was entirely unknown among the Indians, and that Tsonnonthouan himself had no manner of pretensions to it; he stopt my mouth, by telling me, that an English reader would have a much great curiosity about the adventures of a crowned head, than a private person; and that he would now naturally expect a great deal of court-scandal, and secret history. I submitted, thinking it needless to tell him that the work itself would utterly disappoint all such expectations, for, as I ob- [viii] served before, a bookseller never looks father than the title-page.

We had next a small difference about what is called the running title, which, tho' in the body of the book, the bookseller reckoned was within his province, and under his jurisdiction. I must confess, from long habit, I have contracted a sort of fondness for the very name of Tsonnonthouan; I therefore moved that my favourite word should be on the top of every page. But the wise bookseller was entirely of a contrary opinion. Notwithstanding, said he, we have now a very saleable title, yet, for for all that, we cannot ensure the sale; now, if we have a running title, we can never alter the title-page; whereas, if we have not, and we find it does not sell under this title, it is only printing another half sheet, and giving it what other title we please, so that at last it must certainly go off: we may even call it, added he, A Continuation of the Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy. I submitted to superior judgment in this as well as the former article; but I think it my duty, at the same time, to acquaint the publick with the snare that is [l]aid for them, and that if they do not take off this impression under its present [ix] title, which, however, I would advise them by all means to do, they may some time hence find themselves lulled asleep with the first and second volumes of the grave and solemn Tsonnonthouan, when they expect to be tickled to death with the seventh and eighth volumes of the witty and facetious Tristram Shandy.

The important article of the title, both standing and running, being thus settled, we had afterwards a third and more violent dispute about the price. He asked me what price I intended to set upon it? I answered, half-a-crown a volume sewed. That can never be, said he, there are only eight or nine sheets in each volume; whereas, by all the rules of bookselling, there ought to be, at least, ten or eleven sheets; in short, I cannot, in conscience, sell it for more than two shillings a volume. I told him, that was too little, considering this book was every way an original, and had cost me a great deal of pains and trouble, having been almost my whole life-time in planning it, and having spent many years in executing this small part of it. All stuff! mere stuff! said the bookseller, do you think we regard a work's being an original? or that your having been at great pains, or spent much time, in in- [x] venting and composing it, will compensate for its wanting the proper number of sheets required in the trade? In answer to this, I observed, that there was much more sold matter, and real reading in each volume, than in most half-crown, or even three shilling books that were now published. I grant it, returned he, but that is the very thing I find fault with; however, you are not so much to blame as your printer, who must either be a fool, or know nothing of his business; in short, there is as much letter-press here, so a bookseller, it seems, calls matter, as, if it had been properly managed, would have made four of Tristram Shandy's volumes: had I the printing of it, what with contracting the page, and putting distances between the lines, I should have sold it among the trade, with more credit for eight shillings, than I now can for four. Besides, continued he, by this foolish manner of printing your Tsonnonthouan, you have lost a fine opportunity of being witty, as well as of encreasing your profits. I own, I never read the book, but I have been told, by very good judges, that a great deal of Tristram Shandy's wit consists in the distance between his lines, in the shortness of his chapters and para- [xi] graphs, in the great number of his breaks and dashes, in his blank leaves, and even in misreckoning his pages; and, had you used these methods, they would have likewise swelled your book to its proper size; but, as the matter now stands, I tell you again, my conscience, as a bookseller, will not suffer me to take more than four shillings for each volume. Finding that the tenderness of the bookseller's conscience was here like to be prejudicial to my interest, I was obliged to use my authority as an editor, and tell him, he might sell it for six pence, if he pleased, but that he should account to me, at the rate of five shillings for every copy he disposed of; at the same time, in order to sweeten this peremptory intimation, I promised him, that if it ever came to a second edition, I should remove all the scruples of his conscience, and encrease the size and wit of the performance; which latter I feared was most necessary, by putting what distances between the lines he pleased, by splitting the chapters and paragraphs as he thought proper; and, lastly, by inserting as many breaks and dashes, and leaving as many blank pages as he should advise. Upon hearing this, he consented, [xii] though with infinite reluctances, to sell at a crown.

In justice to my bookseller, I could not help premising these things. If there is any merit in the title page, it is entirely his; he being the author of every thing there, except the Greek motto. But, if there are any demerits in the book itself, or in its price, the blame must entirely fall upon me; for, of the first, he is entirely ignorant; and the latter, the reader may see, was much against his inclination, and, indeed, hath done violence to his conscience. However, it may be seen from hence, that, according to a bookseller, the merit of a book consists altogether in its title; and its value solely depends on the quantity of paper that is blotted. I wish this opinion may not prevail among other others of men, as well as booksellers.

The once celebrated name of Tristram Shandy having been accidentally mentioned, an observation occurs, which I cannot help making. What a memento mori ought the fate of this author be to all those who may hereafter possess the approbation of the publick, and how unstable a thing is any literary fame, which has not stood the test of a century? And yet [xiii] after all, the profound quiet and sleep which this writer at present enjoyeth, is as hard to be accounted for as that violent tempest and hurricane, drawing almost every thing within its vortex, which he raised in the republick of letters at his first appearance. Speaking impartially, his two last volumes are perhaps as injuriously neglected, as his first were injudiciously exalted. A true wit and original fancy, joined with a pure and elegant stile, he has unfortunately debased with a perpetual affectation, an irksome ostentation, and often an important straining at wit; which must be disgustful to every reader of taste, and must have been so to himself, if ever he gave his rapsodies a perusal at a cool moment. The publick is said to be ever impartial, and perhaps, even in this case, they have been so on the whole. Yet one would rather rise up gradually to a solid and lasting reputation, like the spreading oak, than sprout up suddenly, and send forth the fairest flowers and blossoms, like a perennial plant, and, when the season is over, wither as suddenly, and be trodden under foot.

Whenever an author speaks seriously of himself, he always does it with a bad grace. It is therefore with reluctance I [xiv] add, that if I have not been able to reach all the excellencies of this truly ingenious author, whom, by the by, I never proposed to imitate, this work, having been planned, and indeed begun, long before his was heard of; yet I have at least avoided his above-mentioned capital fault. There is not, I will venture to say, in the following sheets, the smallest affectation or ostentation of wit; if there is any wit, the reader is left to find it out; this is always an author's best policy, for a reader is much better pleased with the wit he discovers himself, than with that which is pointed out to him; he gives himself credit for it, and he is grateful on that account to the author, often imputing wit to him where he never intended it, and which he never thought of.

But if I have shunned one rock Mr. S. has split upon, I have not been able to avoid another, not owing to design indeed, as seems to have been his case, but owing to my own particular situation and disposition; I mean the presumption of publishing an imperfect work to the world, and perhaps, the still great presumption of hoping the publick may expect a continuation of it. I do not intend it as a praise, when I say, that the following sheets, tho' the [xv] consequence of a design conceived in early youth, have been as many years in executing under my hands, as they would probably have been weeks under those of a bookseller's labourer; in short, I found, before I could compleat my design, at the rate I went on, more years would elapse than I could expect to live. Whether it shall ever be compleated, is left to time and chance; but if in the mean time any Grubstreet continuator should undertake it, he will find hints in the first chapter, to which he is heartily welcome, and if he does, I sincerely wish him all the success he may deserve.

However, one thing, I think, I may venture to add; if this work is to be deemed altogether a fiction and romance, yet, as appears from the very first chapter, a regular plan is laid down, which cannot be departed from, and consequently it must as last come to an end, and was never intended to be an everlasting work like that of Tristram Shandy, and no design was entertained of writing as long as the author could preserve his credit with the publick, or secure its attention. But as to the real scope or moral of this performance, I beg to be excused from saying any thing, imitating herein the exam- [xvi] ple of the Indians, who, though full well acquainted with the nature of Tsonnonthouan's flight from the tree, and ascension to the country of souls; yet said nothing to him about it, and left him to find out the secret himself. Yet so far I will take upon me to say, that whatever prejudiced and interested persons may think of it, it is such as a philosopher, a man of virtue, and one who is a friend to, as well as lover of his species, may boldly, and without a blush, avow.

From A Catalogue of Books, Ancient and Modern (Edinburgh, 1793), p. 193.

From A Catalogue of the Curious and Extensive Library of the late James Bindley, Esq., F.S.A. (1818), p. 74.

Preface:

[v] The Bookseller having insisted on his prerogative of writing the Title-Page, I wish he had also written the Preface; it would have saved me a task I am by no means fond of. In justice he ought to have done it, for his Title-Page hath rendered a Preface necessary. But he must be excused, on this account; a Preface is always supposed to have some relation to the work it ushers into the world; now a bookseller having commonly as great an aversion as reading the trash he sells to his customers, as a physician has at taking the trash he prescribes to his patients, it is not to be expected a man should write about that which he knows nothing of. This, I can safely say, is the case with my bookseller; I can aver he has not as yet read a sentence of the following work, and in all probability never will. But it [vi] is quite otherwise with the title, as it is by the merits of that alone he thinks he sells the book; and indeed he is in the right to think so, for he seldom knows any thing more of the matter. I have heard a bookseller say he had purchased a pamphlet for half a guinea, tho' he knew not what the pamphlet contained, but he was sure he had made a good bargain, for the title page alone was worth double the money. Indeed it is no wonder that booksellers are the best judges and authors of title-pages in the world, the whole force of their genius, and bent of their study, being directed to nothing else, except, sometimes, a few strictures on the paper, print, and binding; and when a man applies himself entirely to one science, he must necessarily excell in it. For this reason I submitted every thing respecting the title-page to the bookseller; indeed he made enquiries about nothing else, excepting the price. When I first carried him the following sheets in manuscript, he asked me what title I proposed? I made answer, The Life and Adventures of Tsonnonthouan, a Roundheaded Indian. He objected to this as too simple; we must call it Memoirs, said he, for that word implies something of secrecy, and the [vii] publick is always glad of being let into a secret. This being assented to, he next hinted that the hero ought to be dignified with some pompous appellation; I proposed that of Chief of the Roundheads, though not strictly and historically true. The sagacious bookseller was not altogether pleased with this; he said, it referred to something outlandish, and besides, we had but a slender idea of such an office in this country. I was very sensible of the solidity of this objection, so left the matter entirely to himself. Upon which he immediately dubbed Tsonnonthouan King; a name, which notwithstanding some late incidents, has still some regard paid to it, amongst us. It was in vain for me to object that such an office was entirely unknown among the Indians, and that Tsonnonthouan himself had no manner of pretensions to it; he stopt my mouth, by telling me, that an English reader would have a much great curiosity about the adventures of a crowned head, than a private person; and that he would now naturally expect a great deal of court-scandal, and secret history. I submitted, thinking it needless to tell him that the work itself would utterly disappoint all such expectations, for, as I ob- [viii] served before, a bookseller never looks father than the title-page.

We had next a small difference about what is called the running title, which, tho' in the body of the book, the bookseller reckoned was within his province, and under his jurisdiction. I must confess, from long habit, I have contracted a sort of fondness for the very name of Tsonnonthouan; I therefore moved that my favourite word should be on the top of every page. But the wise bookseller was entirely of a contrary opinion. Notwithstanding, said he, we have now a very saleable title, yet, for for all that, we cannot ensure the sale; now, if we have a running title, we can never alter the title-page; whereas, if we have not, and we find it does not sell under this title, it is only printing another half sheet, and giving it what other title we please, so that at last it must certainly go off: we may even call it, added he, A Continuation of the Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy. I submitted to superior judgment in this as well as the former article; but I think it my duty, at the same time, to acquaint the publick with the snare that is [l]aid for them, and that if they do not take off this impression under its present [ix] title, which, however, I would advise them by all means to do, they may some time hence find themselves lulled asleep with the first and second volumes of the grave and solemn Tsonnonthouan, when they expect to be tickled to death with the seventh and eighth volumes of the witty and facetious Tristram Shandy.

The important article of the title, both standing and running, being thus settled, we had afterwards a third and more violent dispute about the price. He asked me what price I intended to set upon it? I answered, half-a-crown a volume sewed. That can never be, said he, there are only eight or nine sheets in each volume; whereas, by all the rules of bookselling, there ought to be, at least, ten or eleven sheets; in short, I cannot, in conscience, sell it for more than two shillings a volume. I told him, that was too little, considering this book was every way an original, and had cost me a great deal of pains and trouble, having been almost my whole life-time in planning it, and having spent many years in executing this small part of it. All stuff! mere stuff! said the bookseller, do you think we regard a work's being an original? or that your having been at great pains, or spent much time, in in- [x] venting and composing it, will compensate for its wanting the proper number of sheets required in the trade? In answer to this, I observed, that there was much more sold matter, and real reading in each volume, than in most half-crown, or even three shilling books that were now published. I grant it, returned he, but that is the very thing I find fault with; however, you are not so much to blame as your printer, who must either be a fool, or know nothing of his business; in short, there is as much letter-press here, so a bookseller, it seems, calls matter, as, if it had been properly managed, would have made four of Tristram Shandy's volumes: had I the printing of it, what with contracting the page, and putting distances between the lines, I should have sold it among the trade, with more credit for eight shillings, than I now can for four. Besides, continued he, by this foolish manner of printing your Tsonnonthouan, you have lost a fine opportunity of being witty, as well as of encreasing your profits. I own, I never read the book, but I have been told, by very good judges, that a great deal of Tristram Shandy's wit consists in the distance between his lines, in the shortness of his chapters and para- [xi] graphs, in the great number of his breaks and dashes, in his blank leaves, and even in misreckoning his pages; and, had you used these methods, they would have likewise swelled your book to its proper size; but, as the matter now stands, I tell you again, my conscience, as a bookseller, will not suffer me to take more than four shillings for each volume. Finding that the tenderness of the bookseller's conscience was here like to be prejudicial to my interest, I was obliged to use my authority as an editor, and tell him, he might sell it for six pence, if he pleased, but that he should account to me, at the rate of five shillings for every copy he disposed of; at the same time, in order to sweeten this peremptory intimation, I promised him, that if it ever came to a second edition, I should remove all the scruples of his conscience, and encrease the size and wit of the performance; which latter I feared was most necessary, by putting what distances between the lines he pleased, by splitting the chapters and paragraphs as he thought proper; and, lastly, by inserting as many breaks and dashes, and leaving as many blank pages as he should advise. Upon hearing this, he consented, [xii] though with infinite reluctances, to sell at a crown.

In justice to my bookseller, I could not help premising these things. If there is any merit in the title page, it is entirely his; he being the author of every thing there, except the Greek motto. But, if there are any demerits in the book itself, or in its price, the blame must entirely fall upon me; for, of the first, he is entirely ignorant; and the latter, the reader may see, was much against his inclination, and, indeed, hath done violence to his conscience. However, it may be seen from hence, that, according to a bookseller, the merit of a book consists altogether in its title; and its value solely depends on the quantity of paper that is blotted. I wish this opinion may not prevail among other others of men, as well as booksellers.

The once celebrated name of Tristram Shandy having been accidentally mentioned, an observation occurs, which I cannot help making. What a memento mori ought the fate of this author be to all those who may hereafter possess the approbation of the publick, and how unstable a thing is any literary fame, which has not stood the test of a century? And yet [xiii] after all, the profound quiet and sleep which this writer at present enjoyeth, is as hard to be accounted for as that violent tempest and hurricane, drawing almost every thing within its vortex, which he raised in the republick of letters at his first appearance. Speaking impartially, his two last volumes are perhaps as injuriously neglected, as his first were injudiciously exalted. A true wit and original fancy, joined with a pure and elegant stile, he has unfortunately debased with a perpetual affectation, an irksome ostentation, and often an important straining at wit; which must be disgustful to every reader of taste, and must have been so to himself, if ever he gave his rapsodies a perusal at a cool moment. The publick is said to be ever impartial, and perhaps, even in this case, they have been so on the whole. Yet one would rather rise up gradually to a solid and lasting reputation, like the spreading oak, than sprout up suddenly, and send forth the fairest flowers and blossoms, like a perennial plant, and, when the season is over, wither as suddenly, and be trodden under foot.

Whenever an author speaks seriously of himself, he always does it with a bad grace. It is therefore with reluctance I [xiv] add, that if I have not been able to reach all the excellencies of this truly ingenious author, whom, by the by, I never proposed to imitate, this work, having been planned, and indeed begun, long before his was heard of; yet I have at least avoided his above-mentioned capital fault. There is not, I will venture to say, in the following sheets, the smallest affectation or ostentation of wit; if there is any wit, the reader is left to find it out; this is always an author's best policy, for a reader is much better pleased with the wit he discovers himself, than with that which is pointed out to him; he gives himself credit for it, and he is grateful on that account to the author, often imputing wit to him where he never intended it, and which he never thought of.

But if I have shunned one rock Mr. S. has split upon, I have not been able to avoid another, not owing to design indeed, as seems to have been his case, but owing to my own particular situation and disposition; I mean the presumption of publishing an imperfect work to the world, and perhaps, the still great presumption of hoping the publick may expect a continuation of it. I do not intend it as a praise, when I say, that the following sheets, tho' the [xv] consequence of a design conceived in early youth, have been as many years in executing under my hands, as they would probably have been weeks under those of a bookseller's labourer; in short, I found, before I could compleat my design, at the rate I went on, more years would elapse than I could expect to live. Whether it shall ever be compleated, is left to time and chance; but if in the mean time any Grubstreet continuator should undertake it, he will find hints in the first chapter, to which he is heartily welcome, and if he does, I sincerely wish him all the success he may deserve.

However, one thing, I think, I may venture to add; if this work is to be deemed altogether a fiction and romance, yet, as appears from the very first chapter, a regular plan is laid down, which cannot be departed from, and consequently it must as last come to an end, and was never intended to be an everlasting work like that of Tristram Shandy, and no design was entertained of writing as long as the author could preserve his credit with the publick, or secure its attention. But as to the real scope or moral of this performance, I beg to be excused from saying any thing, imitating herein the exam- [xvi] ple of the Indians, who, though full well acquainted with the nature of Tsonnonthouan's flight from the tree, and ascension to the country of souls; yet said nothing to him about it, and left him to find out the secret himself. Yet so far I will take upon me to say, that whatever prejudiced and interested persons may think of it, it is such as a philosopher, a man of virtue, and one who is a friend to, as well as lover of his species, may boldly, and without a blush, avow.

Sunday, June 21, 2015

Links & Reviews

I'm more likely than usual to have missed relevant links this week, since I had the great pleasure of taking a Rare Book School course (The History of European & American Papermaking, taught by Tim Barrett and John Bidwell), and was thus paying less attention than usual to whatever was crossing the transom. So feel free to send along anything I missed and I'll be sure to add it next week. The course was absolutely fantastic!

- David Leonard, the director of administration and technology at the Boston Public Library, was named interim BPL president this week. Board member John T. Hailer was chosen as the new chair of the library's board. Author Dennis Lehane also submitted his resignation from the BPL board this week.

- Rebecca Rego Barry has a piece in the Guardian this week about the planned sale of Edwin Booth's copy of the Second Folio at Sotheby's on Friday. The volume was consigned by the Manhattan's Players Club, but failed to find a buyer.

- At the same sale, which realized more than $3.5 million, the Gutenberg Bible fragment sold by the Jewish Theological Seminary did better than anticipated, fetching $970,000, and a copy of Virgil signed by Declaration of Independence signer Thomas Lynch, Jr. sold for $43,750.

- The WSJ ran a piece on the "value" of a Gutenberg Bible, a complete copy of which hasn't been to auction since 1978.

- Two books stolen from the National Library of Sweden by a senior librarian there in the 1990s were repatriated this week at a ceremony in Manhattan. Both had been acquired by New York booksellers between 1999 and 2001 from the German auction house Ketterer Kunst; one had been sold on to Cornell University. The library maintains a list of the books still missing. The librarian, Anders Burius, committed suicide in 2004 after confessing to the thefts.

- From Yale, a more detailed story on the recent hyperspectral analysis of the 1491 Martellus map.

- The debate over the play Double Falsehood continues, with a new linguistic study outlined in a New Yorker blog post by Alastair Gee. The study, based on the use of particular "function words," finds that Shakespeare and John Fletcher's linguistic fingerprints predominate in the play's text.

- From Eric Kwakkel, "Medieval Letter-People."

- New to me: the Library of Virginia has launched a crowdsourced transcription project, allowing folks to work on small segments of the library's collections.

- The University of Michigan has digitized a collection of more than 2,000 political posters.

Reviews

- Robert Hutchinson's The Audacious Crimes of Colonel Blood; review by Jessie Childs in the TLS.

- Deborah Lutz's The Brontë Cabinet; review by Claudia Fitzherbert in the Telegraph.

- David Leonard, the director of administration and technology at the Boston Public Library, was named interim BPL president this week. Board member John T. Hailer was chosen as the new chair of the library's board. Author Dennis Lehane also submitted his resignation from the BPL board this week.

- Rebecca Rego Barry has a piece in the Guardian this week about the planned sale of Edwin Booth's copy of the Second Folio at Sotheby's on Friday. The volume was consigned by the Manhattan's Players Club, but failed to find a buyer.

- At the same sale, which realized more than $3.5 million, the Gutenberg Bible fragment sold by the Jewish Theological Seminary did better than anticipated, fetching $970,000, and a copy of Virgil signed by Declaration of Independence signer Thomas Lynch, Jr. sold for $43,750.

- The WSJ ran a piece on the "value" of a Gutenberg Bible, a complete copy of which hasn't been to auction since 1978.

- Two books stolen from the National Library of Sweden by a senior librarian there in the 1990s were repatriated this week at a ceremony in Manhattan. Both had been acquired by New York booksellers between 1999 and 2001 from the German auction house Ketterer Kunst; one had been sold on to Cornell University. The library maintains a list of the books still missing. The librarian, Anders Burius, committed suicide in 2004 after confessing to the thefts.

- From Yale, a more detailed story on the recent hyperspectral analysis of the 1491 Martellus map.

- The debate over the play Double Falsehood continues, with a new linguistic study outlined in a New Yorker blog post by Alastair Gee. The study, based on the use of particular "function words," finds that Shakespeare and John Fletcher's linguistic fingerprints predominate in the play's text.

- From Eric Kwakkel, "Medieval Letter-People."

- New to me: the Library of Virginia has launched a crowdsourced transcription project, allowing folks to work on small segments of the library's collections.

- The University of Michigan has digitized a collection of more than 2,000 political posters.

Reviews

- Robert Hutchinson's The Audacious Crimes of Colonel Blood; review by Jessie Childs in the TLS.

- Deborah Lutz's The Brontë Cabinet; review by Claudia Fitzherbert in the Telegraph.

Sunday, June 14, 2015

Links & Reviews

- James Billington, Librarian of Congress since 1987, will retire effective 1 January 2016. The NYTimes piece on the announcement includes a range of critiques of Billington, from Robert Darnton, Paul Courant, and others. The Washington Post story on Billington's retirement was posted in the paper's style blog; it notes that reaction to Billington's announcement inside the library was "almost gleeful" but also includes praise from David Rubenstein and several members of Congress.

- On Friday the NYTimes wrote about several of the possible candidates to replace Billington (though Amy Ryan's inclusion in the list, given her recent resignation, seems a bit strange). The piece notes that we are likely months away from a nomination.

- Kevin Mac Donnell asked publicly via the Exlibris list on Saturday whether Billington's retirement is connected to the controversy over a book published last fall, Mark Twain's America, which was found to be largely plagiarized from other sources (and about which a lawsuit is pending).

- Jeffrey Rudman, chair of the Boston Public Library's board of trustees, has resigned effective 3 July.

- Six Harper Lee letters failed to sell at auction on Friday, with bidding stalling out at $90,000.

- Issues of the New-York Historical Society Quarterly from 1917 through 1984 are now available online via the New York Heritage digital collection.

- The Beinecke Library has digitized its collection of Jonathan Edwards manuscripts.

- Molly Hardy has a wrap-up post about last week's Digital Antiquarian Conference at Workshop at the AAS, and attendee Carl Robert Keyes wrote up the conference and workshop for The Junto.

- David Seaman, currently associate librarian for information management at Dartmouth College, has been selected as the University librarian and dean of the Syracuse University Libraries.

- Greg Eow, currently the Charles Warren Bibliographer for American History at Harvard, has been appointed the new Associate Director for Collections in the MIT Libraries.

- The NYTimes covers scholar Grigory Kessel's efforts to digitally reunite the dispersed leaves of the oldest known manuscript of Galen's "Simple Drugs," overwritten in the eleventh century and known now as the Syriac Galen Palimpsest.

- David Whitesell writes at Notes from Under Grounds about UVA's recent acquisition of a papyrus fragment, and about the difficult ethical considerations that accompany this purchase.

- Over at the Cambridge University Library Special Collections blog, Liam Sims writes about M.R. James' books and his library, noting that Cambridge recently acquired a copy of James' Wailing Well.

Reviews

- Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's The Story of Alice; reviews by Michael Wood in the NYTimes and Michael Dirda in the WaPo.

- William Marvel's Autocrat; review by Harold Holzer in the WSJ.

- On Friday the NYTimes wrote about several of the possible candidates to replace Billington (though Amy Ryan's inclusion in the list, given her recent resignation, seems a bit strange). The piece notes that we are likely months away from a nomination.

- Kevin Mac Donnell asked publicly via the Exlibris list on Saturday whether Billington's retirement is connected to the controversy over a book published last fall, Mark Twain's America, which was found to be largely plagiarized from other sources (and about which a lawsuit is pending).

- Jeffrey Rudman, chair of the Boston Public Library's board of trustees, has resigned effective 3 July.

- Six Harper Lee letters failed to sell at auction on Friday, with bidding stalling out at $90,000.

- Issues of the New-York Historical Society Quarterly from 1917 through 1984 are now available online via the New York Heritage digital collection.

- The Beinecke Library has digitized its collection of Jonathan Edwards manuscripts.

- Molly Hardy has a wrap-up post about last week's Digital Antiquarian Conference at Workshop at the AAS, and attendee Carl Robert Keyes wrote up the conference and workshop for The Junto.

- David Seaman, currently associate librarian for information management at Dartmouth College, has been selected as the University librarian and dean of the Syracuse University Libraries.

- Greg Eow, currently the Charles Warren Bibliographer for American History at Harvard, has been appointed the new Associate Director for Collections in the MIT Libraries.

- The NYTimes covers scholar Grigory Kessel's efforts to digitally reunite the dispersed leaves of the oldest known manuscript of Galen's "Simple Drugs," overwritten in the eleventh century and known now as the Syriac Galen Palimpsest.

- David Whitesell writes at Notes from Under Grounds about UVA's recent acquisition of a papyrus fragment, and about the difficult ethical considerations that accompany this purchase.

- Over at the Cambridge University Library Special Collections blog, Liam Sims writes about M.R. James' books and his library, noting that Cambridge recently acquired a copy of James' Wailing Well.

Reviews

- Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's The Story of Alice; reviews by Michael Wood in the NYTimes and Michael Dirda in the WaPo.

- William Marvel's Autocrat; review by Harold Holzer in the WSJ.

Sunday, June 07, 2015

Links & Reviews

- For the second week in a row this roundup must lead with the Boston Public Library, but at least some of the news this time around is good. On Thursday afternoon the library announced that the missing prints had been found (by Conservation Officer Lauren Schott), having been misfiled within the library's secure stacks. The Boston Globe ran a full story on the (re)discovery of the prints, followed by a piece focused on the methodical search for the prints and the immediate aftermath.

- This came less than a day after BPL president Amy Ryan submitted her resignation (effective 3 July) following an emergency meeting of the BPL's board; Ryan said that she wanted to "allow the work of the [BPL] to continue without distraction." At the board meeting earlier on Wednesday, Ryan had announced an action plan for collections management, which includes the transfer of 24,000 paper catalog cards to the online catalog over the next year, as well as an item-by-item inventory of the print collection, a full assessment of special collections in advance of a full inventory, and staff redeployment. Ryan noted that a high priority for many years was on acquisition, rather than cataloging: "For its nearly 170-year history, the collecting philosophy of the [BPL] has been to acquire as much as possible. Before 2009 a priority had not been placed on cataloging or on access to those materials by the public. In the 1980s there were substantial financial resources and grants available to libraries across the U.S. to automate their collections and convert catalog cards into electronic records, however, the BPL did not take advantage of the financial resources at that time."

- Following the recovery of the prints, at least one BPL trustee, Paul La Camera, told the Boston Herald that he wants Ryan to remain as president, though Ryan has said that her resignation stands. Boston City Councilor Stephen J. Murphy has called for the entire board of trustees to resign, and in an editorial, the Boston Herald also called for more resignations, faulting Ryan for blaming her predecessors (for acquiring without cataloging) and saying "Frankly it's the board, which has had way too cozy a relationship with Ryan over the years, that needs a house-cleaning. And that needs to happen before her successor is chosen. That coziness, that lack of independence, that absence of people willing to ask tough questions and demand straight answers—in fact, that ongoing lack of transparency in all that the BPL does is at the heart of its problems. ... This is about coming up with new ways of doing business in a digital age to protect the library's many treasures and finding ways to make them more—not less—accessible. [Boston mayor Martin] Walsh needs a new generation of leaders on the board who can help make that happen. Ryan's departure should be only the beginning."

- It's also worth noting the release of an "Operational and Financial Assessment" by Chrysalis Management [PDF], dated 15 May 2015, which highlights major deficiencies in inventory control and discoverability (p. 7) among other areas. Just 19% of the BPL's research and special collections are currently searchable online, the report maintains (including fewer than 2% of the manuscripts, 16% of rare books, and 6% of maps and atlases). This report calls recommends that the library "Complete full inventory of owned assets, deaccession non-core special collections, pause purchasing in rare books and prints, refocus special collections away from acquisitions and toward discoverability" (p. 15). Read the full report for more in-depth analysis, not all of which makes good institutional sense but some of which certainly does.

- Two books stolen from the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian) in the late 1990s have been recovered following a four-year investigation. No word, however, on whether any charges will be filed.

- Penn has acquired a fragmentary manuscript almanac from 1746/7 with a possible attribution to David Rittenhouse.

- A rare Apple I computer, hand-built by Jobs and Wozniak, turned up at a recycling center near Silicon Valley. The computer was sold for $200,000 and staff at the recycling firm are looking for the woman who brought in the computer, so that they can share half of the proceeds.

- An inscription by Tolkien in a first edition of The Hobbit (which sold for £137,000) was not actually in Elvish (as the auction catalog description had it), but in Old English.

- The Berkeley bookstore Shakespeare & Co. Books closed suddenly this week after 51 years in business, with the store's stock purchased en bloc by Powell's.

- Hyperspectral imaging of the Wadham Gospels has confirmed what ultraviolet imaging showed in the 1970s; that there is a preliminary sketch of St. Matthew at the start of his gospel not visible to the naked eye.

- A remarkable find in Oklahoma: contractors removing chalkboards at a high school discovered earlier chalkboards behind the existing ones, still containing lessons from 1917!

- As part of their Endangered Archives project, the BL has posted images of a series of documents and photographs from the island of Montserrat.

- A guest post by Austin Plann Curley at The Collation outlines "the mystery of gridded paper."

- The AAS has published the Twitterstream from last weekend's Digital Antiquarian Conference.

Reviews

- Michael Pye's The Edge of the World; review by Russell Shorto in the NYTimes.

- Andrea Mays' The Millionaire and the Bard; review by Dennis Drabelle in the WaPo.

- Kenneth C. Davis' The Hidden History of America at War; review by Gregory Crouch in the WaPo.

- Kara Cooney's The Woman Who Would be King; review by Christina Riggs in the TLS.

- Robert Zaretsky's Boswell's Enlightenment; review by Josh Emmons in the LA Review of Books.

- John Palfrey's BiblioTech; review by Michael Lieberman at Book Patrol.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)